Why Sending Trinidad and Tobago’s Most Violent Criminals to El Salvador’s CECOT Could Transform Crime Control

Crime in Trinidad and Tobago remains a pressing challenge, with violent offenses like murder and gang-related activities straining the nation’s resources and public safety. In a recent discussion, Roger Alexander highlighted consultations with El Salvador on innovative crime solutions. One bold idea stands out: transferring Trinidad and Tobago’s most violent criminals to El Salvador’s Terrorism Confinement Center (CECOT). This mega-prison, a cornerstone of El Salvador’s dramatic turnaround from the world’s most violent nation to one of its safest, offers a powerful model for deterrence while sparing Trinidad and Tobago the immense cost of building its own maximum-security facility. Here’s why this approach could be a game-changer.

El Salvador’s Remarkable Transformation: From Violence to Safety

El Salvador’s recent history is a testament to the impact of decisive action. In the early 2010s, the country was synonymous with extreme violence, holding the highest homicide rate globally—peaking at 103 per 100,000 people in 2015. Gangs like MS-13 and Barrio 18 controlled vast territories, extorting businesses, terrorizing communities, and fueling a cycle of bloodshed. By 2022, however, President Nayib Bukele’s aggressive anti-gang strategy, including the state of emergency and mass arrests, slashed homicides by nearly 70% in 2023 alone, with the rate dropping to under 2 per 100,000 by 2025—among the lowest in the Western Hemisphere.

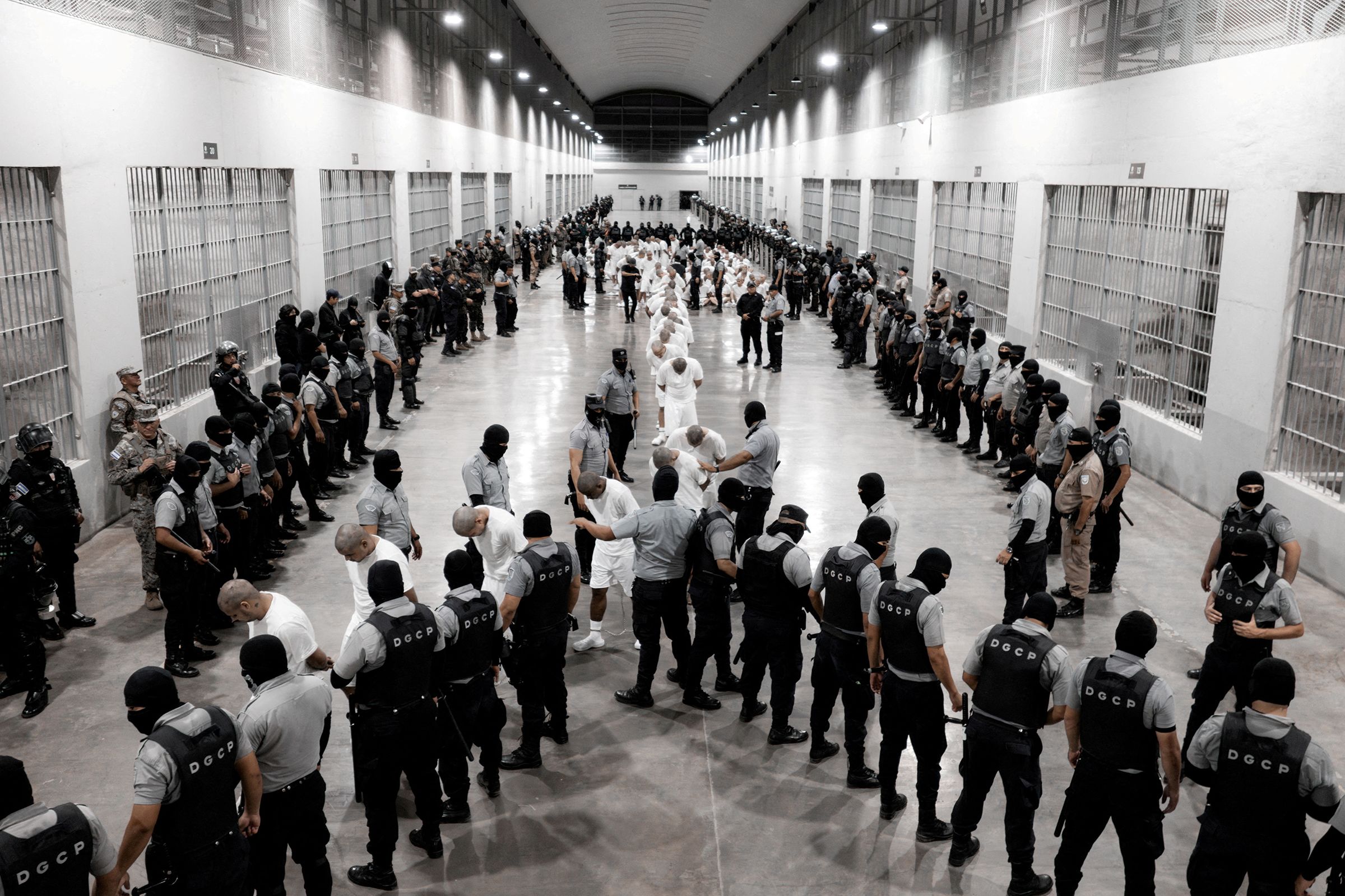

The centerpiece of this transformation is CECOT, a $100 million maximum-security prison opened in 2023 in Tecoluca. Designed to house 40,000 inmates, CECOT confines El Salvador’s most dangerous gang members under strict conditions: 23.5-hour cell confinement, minimal amenities, and no rehabilitation programs, emphasizing punishment and isolation. This facility, coupled with over 85,000 arrests since 2022, has dismantled gang networks, restoring safety to streets once ruled by fear. Salvadorans now report feeling freer, with public approval of Bukele’s policies soaring above 90%

Why CECOT Is a Viable Solution for Trinidad and Tobago

Trinidad and Tobago faces its own crime crisis, with a homicide rate of approximately 30 per 100,000 in recent years and overcrowded prisons exacerbating the problem. Pretrial detainees make up two-thirds of the prison population, and facilities suffer from inadequate sanitation and lighting, fostering a climate of impunity. Building a new maximum-security prison would cost millions—funds that could be better allocated to education, healthcare, or community policing. Instead, partnering with El Salvador to house Trinidad and Tobago’s most violent offenders in CECOT offers a cost-effective, high-impact alternative

Powerful Deterrence Through Harsh Conditions

CECOT’s austere environment—windowless cells, metal bunks without mattresses, and a diet of rice and beans with no meat—sends a clear message: violent crime carries severe consequences. Inmates, described as the “worst of the worst,” face centuries-long sentences with no prospect of release, a stark contrast to Trinidad and Tobago’s often lenient sentencing or prolonged pretrial detentions. For potential offenders in Trinidad and Tobago, the prospect of transfer to CECOT could deter gang involvement or violent acts, mirroring El Salvador’s success in curbing crime through fear of incarceration.

Cost Savings for Trinidad and Tobago

Constructing a facility like CECOT, which cost El Salvador $100 million, is a daunting prospect for Trinidad and Tobago’s budget. Maintenance, staffing, and security for a maximum-security prison would further strain resources. El Salvador’s agreement to house U.S. deportees for $6 million annually suggests a pay-per-inmate model could be negotiated, potentially costing Trinidad and Tobago far less than building and operating its own facility. These savings could fund prevention programs, victim support, or police training, addressing crime’s root causes

Leveraging El Salvador’s Proven Model

El Salvador’s crackdown targeted high-ranking gang members, removing key players from circulation and disrupting criminal networks. Trinidad and Tobago could adopt a similar strategy, identifying and transferring its most dangerous offenders—gang leaders, repeat murderers, and organized crime figures—to CECOT. This would weaken local gangs, reduce prison overcrowding, and allow domestic facilities to focus on rehabilitation for less serious offenders.

Addressing Concerns and Criticisms

Critics, including human rights groups, argue that CECOT’s conditions—overcrowded cells, lack of due process, and allegations of torture—violate international standards. Reports of arbitrary arrests and the detention of innocents, including 8,000 released Salvadorans, raise valid concerns. However, Trinidad and Tobago could mitigate these risks by ensuring rigorous vetting processes, limiting transfers to convicted violent offenders with clear evidence, and negotiating oversight mechanisms with El Salvador. The U.S. partnership, despite controversies over deportee records, demonstrates that international agreements can be structured to prioritize security while addressing legal concerns

Moreover, Trinidad and Tobago’s own prison system is far from ideal, with reports of excessive force, overcrowding, and lengthy pretrial detentions. Transferring the most dangerous inmates to CECOT could alleviate pressure on local facilities, improving conditions for remaining detainees and allowing for reforms focused on rehabilitation.

A Path Forward for Safer Communities

El Salvador’s journey from chaos to safety offers Trinidad and Tobago a blueprint for tackling violent crime. By leveraging CECOT’s capacity and deterrence power, Trinidad and Tobago can sidestep the financial burden of a new prison while sending a strong message to criminals. This strategy aligns with Roger Alexander’s call for innovative solutions, drawing on El Salvador’s expertise to restore public confidence in safety.

To implement this, Trinidad and Tobago should negotiate a transparent agreement with El Salvador, ensuring fair trials and evidence-based convictions for transferees. Public awareness campaigns highlighting CECOT’s conditions could amplify its deterrent effect, discouraging would-be offenders. Meanwhile, redirecting saved funds to community programs and law enforcement could address crime’s social drivers, creating a holistic approach.

Salvador’s transformation proves that strong measures can reclaim safety, and Trinidad and Tobago stands to gain by adopting this model. By combining deterrence, cost savings, and targeted enforcement, this partnership could pave the way for a safer, more secure future.

Disclaimer: This blog post reflects a hypothetical policy proposal based on current data and trends. Any implementation would require careful legal, ethical, and diplomatic considerations